It was a lazy Sunday.

I heard a WhatsApp notification on my phone.

Now, I have a different tone for group notifications, so I could tell it was a notification from one of my WhatsApp groups. Usually, there’s one every couple of hours, especially on Sundays. But this time, it was different. Notifications came with a frequency not representative of a weekend, definitely not Sunday. So I walked with mild urgency into the room where my phone was, only to see this message.

It was unusual.

Unusual because we live in a residential area, away from forests or anything that would even remotely resemble a snake habitat.

There was a flurry of messages on the WhatsApp group, ranging from congratulatory (for the rescuers) to fearful (for our legless reptile visitor). After all, the society was newly formed, and the management committee was cautious with such things because there were toddlers in the building.

I am less knowledgeable about all things serpentine, but I vaguely remember hearing about this concept called ‘Sarp Mitra’ (translated as ‘Friends of Snake’). I knew some folks could handle snakes more elegantly than others, but I did not know one myself.

So, I did what I do best. Google.

Sarpamitras are volunteers who protect and safeguard snakes. They play a crucial role in mitigating the snakebite problem in India. They are often volunteers who work closely with local authorities and healthcare providers to safely remove snakes from populated areas and release them back into the wild. Additionally, Sarpamitras serve as educators, dispelling myths and misconceptions about snakes and snakebites and contributing to public awareness and prevention efforts. Their work is vital.

What’s with India and Snakes, though?

India's diverse geography includes many tropical and subtropical regions, making it a suitable habitat for various snake species. The country's varied landscapes —from dense forests and wetlands to agricultural fields — provide ample opportunities for snakes to thrive. The warm, humid climate is particularly conducive to the reptiles. Additionally, the coexistence of human settlements with natural habitats often leads to frequent human-snake interactions. This geographical and climatic suitability, combined with human encroachment into snake habitats, contributes to the high incidence of snakebites in India.

You see, I have lived in a predominantly urban India, where ‘snakes’ as a topic does not enter the conversation, at least not in the context of day-to-day.

But rural India?

Well, that is a different ballgame.

Serpentine Chronicles from the Kitchen

In the heart of rural India, where the monsoon season heralds the ritual of 'Perni' [Marathi for sowing season], snakes are as much a part of the landscape as the lush green fields. Encounters with snakes in rural India are not just random events but significant, almost ceremonial occurrences. Now, I am a city boy with very little understanding of rural India. So, I was thinking about who could help me understand the length and breadth of the topic in the context of rural India when my doorbell rang.

I opened the door.

It was my cook.

We exchanged ideas on what the dinner menu could be for the evening and, after some negotiations, agreed on the final course.

I then went back to staring into infinity again.

If only I could speak to someone closely connected to rural India.

That’s when it hit me like a rock that the answer was literally and physically in front of me.

My cook!

Jana Bai, my cook, is a repository when it comes to village wisdom. She also has a knack for presenting the story in a narrative that I consider only second to a movie script.

Rural India is full of stories; my cook narrates them Wes Anderson style.

Moi :

[Marathi] "जना माउशी , तुम्ही आता पेरणीला जाणार ना? एक प्रश्ण विचाराय्चा होता. शेतात साप असतात का?"

[English] “Jana Maushi, I hear you will be visiting your village soon for sowing. Had a quick Q. Are there snakes in the fields?”

Cook : “असतात कि दादा” // “Of course, there are.”

Moi : “मग पेरणी कशी करता तुम्ही?”. // “How do you go about sowing crops then?”

Cook: “देवाचा नाव घ्यायचा अन शेतात उतरायचा“ // “We take the name of God and enter the field.”

Moi: “पण साप चावला तर काय करायचा?” // “But what happens if the snake bites?”

Cook: 'There's a Bhairavnath temple nearby,' she said, 'and in every Bhairavnath temple, there is an individual blessed by the divine. That person and that person only is authorised to suck the venom out of the person bitten by a snake. This entire process takes 3 days. During those 3 days, the victim’s family has to light a Diya at the temple and ensure that the light does not go out.’

Jana Maushi clarified that there is a 95% chance that a crop field filled with water does not have a snake inside. “Where there’s so much water, there’s generally no snake,” she said.

I pointed out that there’s still that 5% chance of getting bitten by a snake.

To which she reminded me that the Bhairavnath temple is always there…..

Cold Blood, Hard Facts

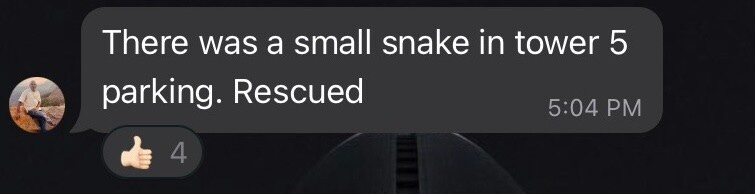

In May 2023, Indian Express reported an unusual story where a renowned doctor from Pune, Dr. Ichaporia, was taken aback to see a patient’s relative carry an actual snake to Sassoon General Hospital in Pune, Maharastra. In hindsight, the relative did a brilliant job capturing the snake and bringing it to the hospital. But it was not very evident to Dr. Ichaporia at the moment.

Stay with me here.

When the patient was brought in, Dr. Ichaporia noticed small puncture wounds on the patient, clearly indicating a snakebite. But there was no way to tell whether the bite was from a venomous or non-venomous snake. This was the 1970s; there was no internet. The closest Dr. Ichaporia was to any legitimate body of knowledge on the topic was in the form of a book on reptiles, safely tucked away in the library of his home, which was 15 minutes away. He knew it was already late; the patient wouldn’t survive that long.

This is when the story takes a turn.

Dr Ichaporia suddenly remembered that a young man was trying to set a record by staying inside a glass enclosure with 72 venomous snakes for 72 hours at BJ Medical College ground in Pune. Could he help?

But for the young man to identify the snake, he needs to “physically” see the snake.

Well, God bless the Patient’s relative; he has the snake!

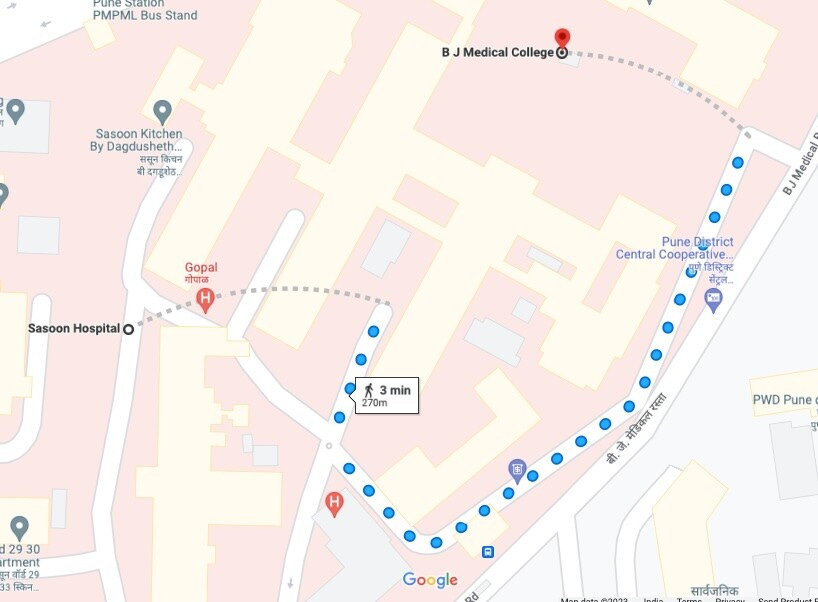

But most importantly - how far is BJ Medical College from Sassoon Hospital? Was the distance shorter than the library of Dr. Ichaporia’s house, which was 15 minutes away?

This is where you start believing in God.

Here is a Google Map screengrab showing the distance between BJ Medical College and Sassoon Hospital in Pune.

3 mins by walk, a minute on the bike.

A minute on the bike!

Dr Icharporia kickstarted his motorcycle, told the relative to hop on with the snake, went straight to the ground, knocked on the glass enclosure where the young man was hanging out with the 72 snakes, and asked if he could identify the snake that the patient’s relative was carrying.

“‘This is a krait!” the young man calmly said (creative liberty taken).

The story, of course, has a happy ending. The 67-year-old patient was sent home after recovering fully.

And as you think all this is very weird and that you rarely read such articles in newspapers, let me assure you that such stories are common in Indian national dailies.

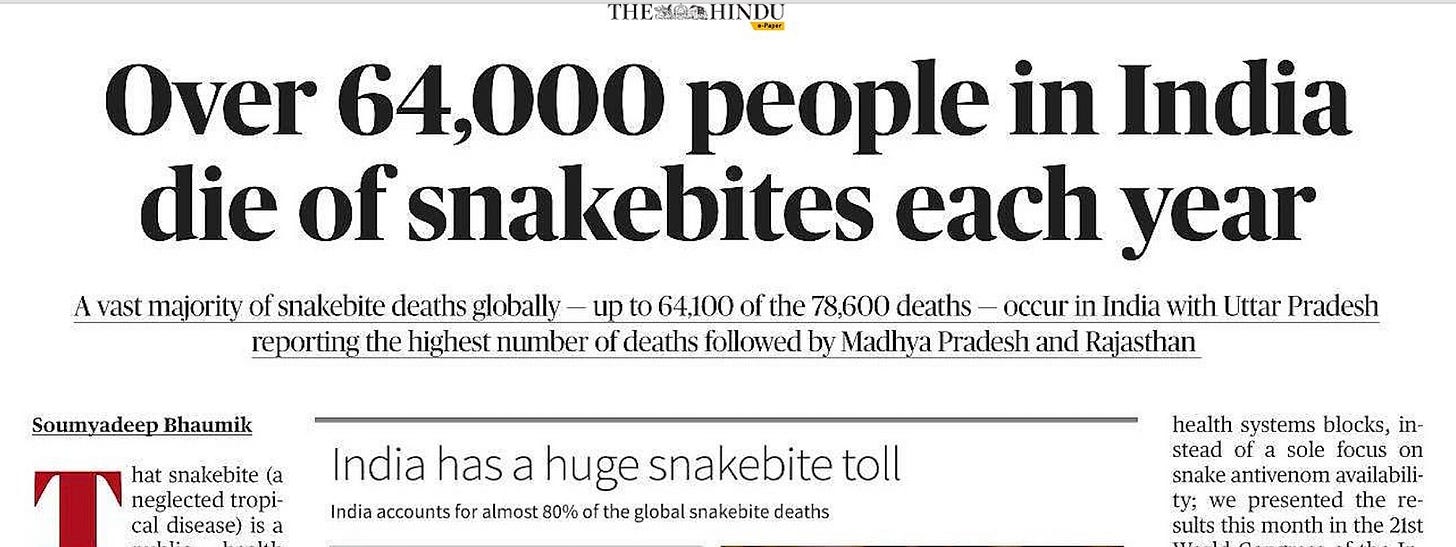

The Hindu reported last year that over 64,000 people in India die of snakebites every year, with Uttar Pradesh reporting the highest number of deaths, followed by Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Indian Express covered a story in August of 2023 where a 4-year-old got bit by a common Krait. She was brought into the hospital just in time, and she lived to see another day.

But not everybody is as lucky as the 4-year-old Ananya. A recent WHO report suggests that an estimated 5.4 million people worldwide are bitten by snakes every year, with 1.8 million to 2.7 million cases of envenomings (poison entering the body). Half of the snakebites in the entire world are from India. It is the most underreported and neglected tropical disease.

Over 130,000 people die each year because of snake bites, and around three times as many amputations and other permanent disabilities are caused by snakebites annually. A nationally representative study noted 45,900 annual snakebite deaths in India.

This is not a good data point. This is an enormous public health problem in India.

So the next logical question is - whether policy is responding to these facts.

The Big 4 and Policy

The Indian Government has obviously realised the gravity of the situation and has been building policy guardrails around it. In collaboration with the Centre for Global Health Research and ICMR, the registrar of India conducted the world’s most extensive study titled the ‘Million Death Study’ on premature mortality. The sample size was 14 million Indians. This report has yielded a lot of good-quality data on snakebites.

This data brings us to the Big 4 - practically dictating Indian policy-making around the topic. I know what you’re thinking, but this is not the Big 4 we know; they’re different and dangerous.

The following group of 4 is considered India’s Big 4 venomous snakes. Known for their ubiquity and stings, these 4 species are responsible for around 90% of snakebites in India. And this is the group the policy may be a bit too focused on.

Common Indian cobra (Naja naja)

Common krait (Bungarus caeruleus)

Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii)

Saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus)

The problem is that the focus on the Big 4 may take away the focus from other venomous snake species in the country.

Snakebite envenoming is recognised as a severe public health issue and is included in national health programs. This recognition is crucial for allocating resources and attention to the problem. The government oversees the production and regulation of antivenom, ensuring its availability and quality. This includes setting standards for antivenom production and distribution. Training programs for healthcare professionals, particularly in rural areas, are conducted to improve the diagnosis and treatment of snakebites. This includes training in the administration of antivenom and managing potential complications.

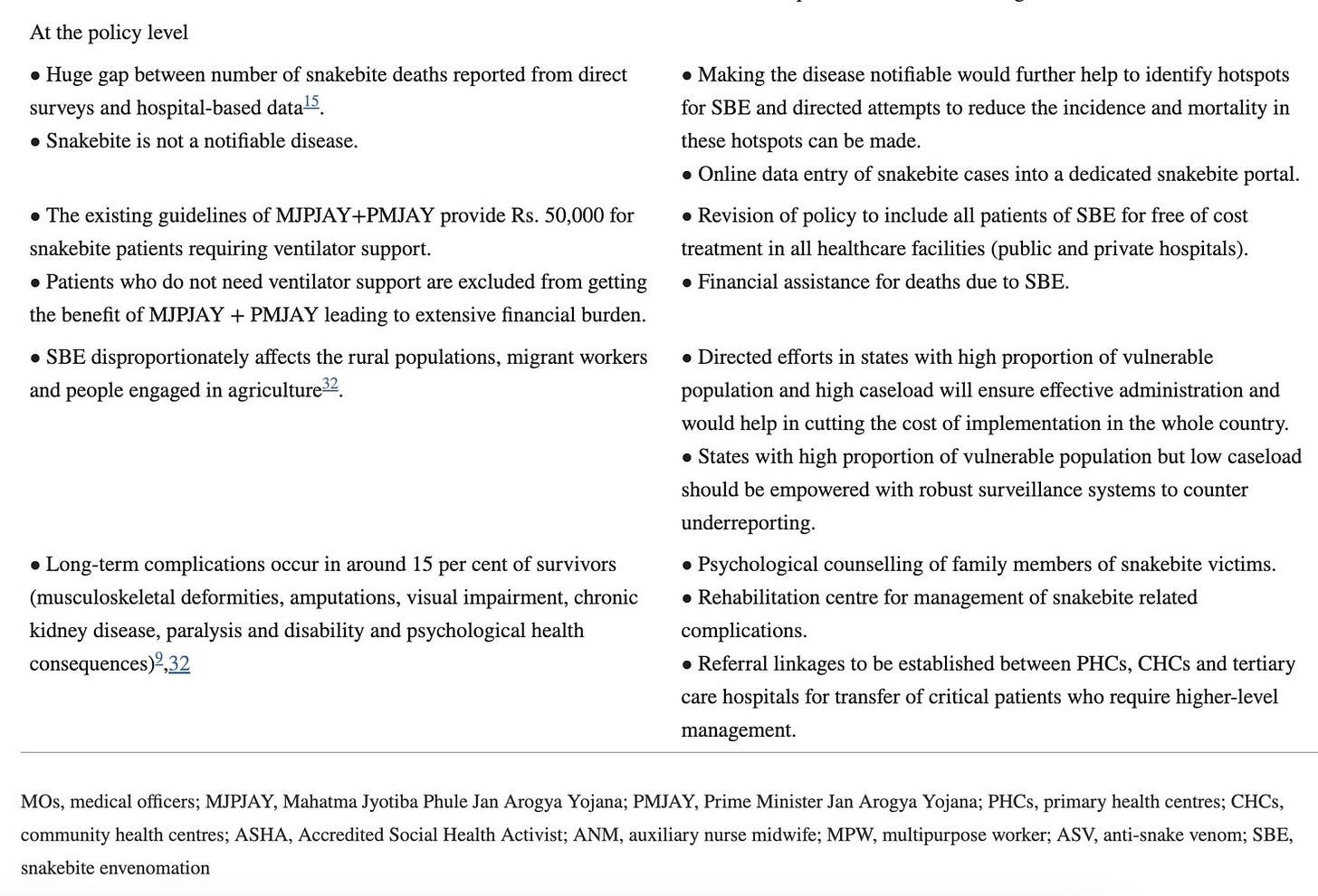

But policy generally responds to data, and we must be cognizant that data here tells only partial truth. This is not because any particular entity is trying to hide data. This is because snakebite is an underreported phenomenon. This high-quality paper elegantly explains why. It also comments on the critical challenges and recommendations for those issues at the community and health systems levels.

Vishal Santra, a West Bengal-based herpetologist, explains that snakebite envenoming is generally ‘considered a poor person’s disease or a rural problem’ because the patients are from marginalised communities or rural backgrounds. And that is where we need divine souls like Dr. Raut, who tirelessly work on the Mission Zero Snake Bite Death project.

Another such divine soul is Dr. Dhirubhai Patel. He has successfully treated over 19,000 snakebite victims in the last 33 years with a 98% success rate at his hospital in Dharampur (Tribal) Taluk, Valsad district, Gujarat.

Rest assured that the Indian Government is spotlighting this public health issue plaguing the country. Indian Council for Medical Research(ICMR) and the National Institute for Research in Reproductive and Child Health (NIRRCH) published a booklet for healthcare workers on managing a Snakebite situation. They also released a very easy-to-understand yet comprehensive flowchart.

This is where I thought - Can we apply technology to this flowchart?

So, I went down the rabbit hole since rabbits are relatively benign.

Can Technology blunt the Serpent strain?

It would be a shame for a tech-forward nation like India to stop at the workflow stage, especially since the requirements-gathering part is behind us.

All we need to do now is to put a technology layer on top of this.

Could we think through the end-to-end workflow and figure out places where technology could help?

I did precisely that.

And here is where we transition into the digital terrain.

Implementing the flowchart as a digital workflow would provide a streamlined and interactive process for health professionals, ensuring timely and accurate management of snakebite cases.

And before you think I am that man with the proverbial hammer called technology, please allow me to elaborate on 7 specific reasons why a technology layer can help here.

Real-time Guidance: A digital workflow can guide healthcare professionals step-by-step, ensuring that all the protocols are followed accurately. For instance, if a patient is symptomatic and shows neurotoxic signs, the workflow would highlight the immediate next steps and provide detailed information on managing such cases.

Data Collection & Analysis: It would enable the collection of real-time data on snakebite incidents, which could be used for epidemiological studies, assessing the efficacy of treatments, and forecasting supply needs for antivenom. This paper recommends making Snakebite envenoming a notifiable disease, which it is not currently. A digital workflow could accelerate the solution.

Integrated Alerts: The system can send alerts for crucial steps, like administering subcutaneous adrenaline as prophylaxis before ASV, ensuring no critical steps are missed.

Resource Availability: The workflow can be linked with inventory management systems to check the required medicines or equipment availability in real time. If an ASV vial is needed, the system could show the current stock and the nearest locations with available stock.

Referral System: For situations where a patient needs to be referred to another facility (like a tertiary care facility for dialysis), the digital workflow can be integrated with a logistics and communication system to facilitate quick patient transfers.

Multimedia Assistance: The digital system can incorporate multimedia elements like videos or animations to demonstrate procedures, aiding in clarity and understanding, especially for less standard procedures.

Local Language Support: Especially in a diverse country like India, with 22 official languages, the workflow can be translated into multiple regional languages, ensuring clarity of instructions for health professionals across the country.

Now, let’s zoom out a bit. Let us move away from the flowchart.

There are 3 broad areas where Technology inclusion in Snakebite envenoming can go a long way (and how).

1. Prevention & Awareness

Snake Activity Predictive Systems: Equip both ASHA workers and local residents with predictive information about snake activities. For feature phone users, send regular SMS alerts about predicted snake activities in specific areas.

Geospatial Mapping Integrated with Hub-and-Spoke: Use the hub-and-spoke healthcare model to monitor snakebite hotspots. Coordinate with peripheral centres to stock antivenom and resources. Local residents and ASHA workers can be alerted about these hotspots through SMS or voice messages.

Audio Awareness Campaigns: Use the power of voice messages or even basic ringtone downloads with messages on snakebite prevention, specially tailored for feature phone users. Imagine getting a call from Amitabh Bachchan, creating awareness about snakebites, especially in rural India. It would stick.

2. Immediate Response & Treatment

Image Recognition for Immediate Diagnosis: An app can be helpful for those with access to smartphones or digital cameras. For feature phone users, a helpline that connects to the nearest 'spoke' for advice can be valuable.

Automated anti-snake venom Dispensing Machines: Place these dispensers at peripheral centres in high-risk zones. ASHA workers and locals can be trained on their use. Alerts about their location and usage can be disseminated via SMS.

Telemedical Connectivity with Hub Hospitals: Establish dedicated helplines that allow both ASHA workers and victims (or their families) to communicate directly with medical experts.

3. Post Bite Management & Rehabilitation

Monitoring Through Voice Feedback: ASHA workers and local residents can report on the condition of snakebite victims through regular voice calls, ensuring continuous monitoring.

Radio Programs on Rehabilitation: Considering the reach of radio in rural areas, regular programs discussing the importance of physiotherapy, precautions, and care for snakebite victims can be broadcast.

Community Support through IVR Systems: Use Interactive Voice Response (IVR) systems to create a platform where survivors can interact, listen to experiences, and get guidance, ensuring emotional support.

Data Collection via SMS and Calls: ASHA workers and local residents can send data about snakebite incidents via SMS or voice calls. This data, when consolidated, can provide valuable insights for future prevention and treatment strategies.

As we harness the power of technology to tackle the snakebite crisis, from AI-driven antivenom distribution to mobile apps for immediate medical guidance, innovation is our only hope for reshaping our battle against this age-old menace.

But while technology offers new solutions, we should not forget that snakes occupy a dominant space in India's collective consciousness— present in Indian mythology, immortalised in movies and games, and almost entering popular culture after shedding their old skin (some pun intended).

Myth, Movies and Modernity

In various cultures and philosophies, the snake is a creature of duality, embodying both life and death, creation and destruction. In Hinduism, the snake is often seen around the neck of Lord Shiva, symbolising the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. It's a creature that's both feared and revered, a paradox that captures the essence of existence itself. In Western thought, the snake in the Garden of Eden represents temptation and the loss of innocence, a cautionary tale that has shaped moral frameworks for generations. In ancient Chinese philosophy, it symbolises transformation and renewal, a creature that sheds its skin only to emerge anew, embodying the eternal cycle of life.

The snake also finds its way into the arts and folklore in India, from the snake charmers of Rajasthan to the iconic "Nagin" dances and films that have captivated audiences for decades. It's a creature that has been romanticised, demonised, and mythologised but never ignored. In the Indian epic, the Mahabharata, the snake even plays a role in the great cosmic game, its presence a constant reminder of the intricate balance between good and evil, life and death. But beyond these cultural imprints, snakebites are a very real and pressing public health issue. As you read - every year, thousands suffer from snakebites, and the problem is especially acute in rural areas where medical facilities are scarce.

As we navigate the complexities of snakebite envenoming, technology offers some solutions. From AI-powered identification apps that instantly recognise snake species and recommend first-aid steps to telemedicine services that provide immediate expert consultations, the digital age equips us with tools to tackle this age-old problem. Today, of all the days, drones can be used to deliver antivenom to remote locations, cutting down crucial time in life-saving procedures. We are closing in on this problem. Let’s get it done!

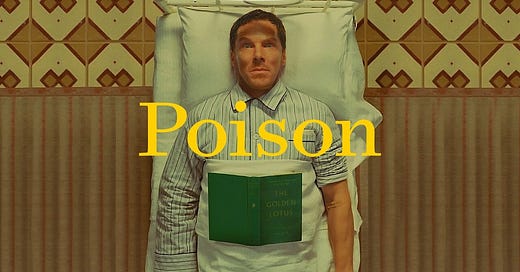

In the Wes Anderson movie ‘Poison’, Benedict Cumberbatch - Harry - is lying on his bed reading a book when he feels something slide over his pyjamas. From the corner of the eye, he sees it’s a common Krait - maybe 10 inches long. The Krait is already on his body. Harry knows only one thing to be done when encountering a snake so close - do not move.

So he does exactly that. Harry waits for hours and hours before he finally finds help in the form of Dev Patel. Dev Patel calls Ben Kingsley, who is playing Dr. Ganderbai. After running out of a few options, Dr Ganderbai decides to administer an anaesthetic to the snake where it lies - on Harry’s stomach - but quickly realises that anaesthetics don’t work on cold-blooded animals. After running through another set of failed options, Dr. Ganderbai finally decides to do the unthinkable. To pull Harry’s sheets and deal with the snake head-on. He does precisely that …….. only to find no snake there ……

But not everyone is as lucky as Harry.

Some of us might actually encounter a snake, hopefully not on our bodies.

And God forbid, next time you see one so close —be it in a field, on a road, or a temple—remember that this creature is not just a symbol or a myth.

It is very real.

Remember what Harry did.

Don't move.

References

Booklet for Snakebite Management: https://nirrh.res.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/English-Booklet.pdf

Flowchart for Snakebite Management: https://nirrh.res.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Management-Flowchart.pdf

WHO Report on Snakebites worldwide: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/snakebite-envenoming

WHO stats on Snakebites in India: https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/snakebite

Million Death Study: https://www.cghr.org/projects/million-death-study-project/